On a tiny farm in Washington State, one woman’s floral workshops have become something of a sensation.

In 2013, Erin Benzakein was a moderately successful flower farmer in Washington’s Skagit Valley, about an hour north of Seattle. She and her husband, Chris, met in high school and had come to the valley a dozen years before, as young urbanites in search of a rural dream, and bought a house on an acre of land. Surrounded by modest farms, the place wasn’t much to look at: vinyl siding, an old garage out back. By then, the couple had a daughter. (A son was born 19 months later.) While Chris found work as a mechanic, Benzakein, who had been a landscaper in Seattle, looked for ways to earn money at home. She tried candle-making, growing baby vegetables, a rainbow-egg business with a hundred chickens. But, she said, “I didn’t make any money, and there was poop everywhere.” The flower idea came five years later, in 2006, when she saw an article by the floral designer Ariella Chezar on arranging clematis. This totally blew Benzakein’s mind, because she’d always considered it an extravagance to cut garden flowers like clematis and bring them inside. They were for display in the garden. Which is largely why almost no one in the Skagit Valley would buy her flowers once she started hustling them. Her total profit the first year was $1,400.

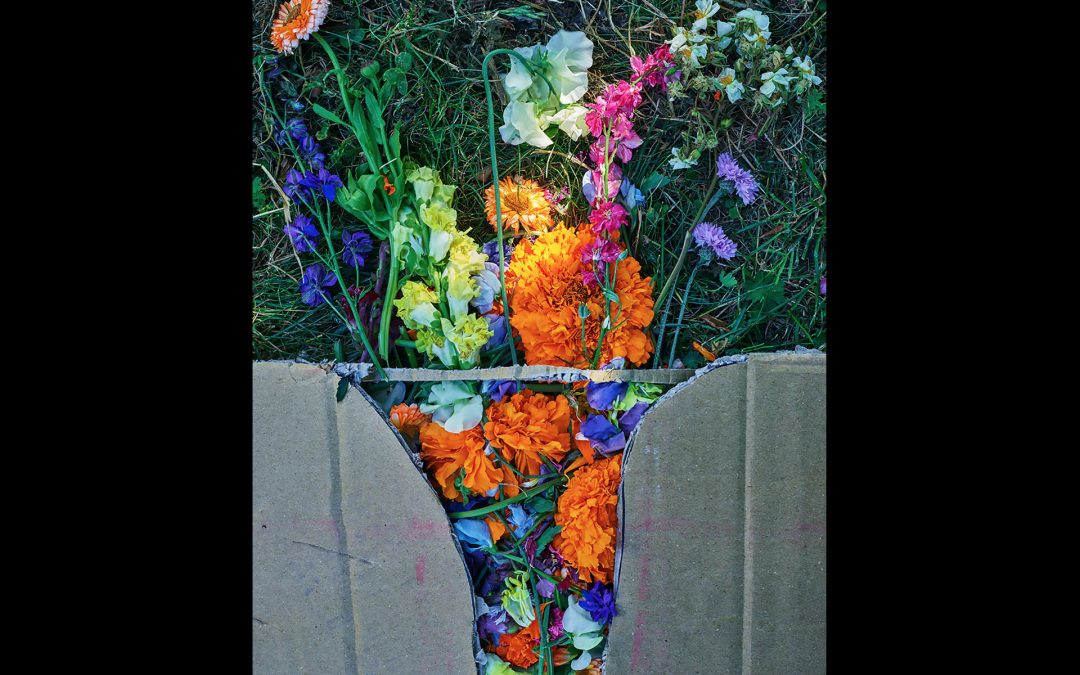

Flowers and Vase #1. Floret Flower Farm, 2017. Abelardo Morell created this image using multiple exposures of different bouquets against a still background.

Meanwhile, the couple had taken out a second mortgage to pay for helicopter-pilot school for Chris. Unable to find a job that gave him enough flight time and with debts to pay off, Chris went back to working on cars. Benzakein, who seems to thrive when she has almost nothing to work with — a quality she traces to her parents, both self-employed — had started freelancing for a trade journal, Growing for Market. She gave herself the target of writing 50,000 words, just so that one day she would feel confident enough to write a book — a goal she fulfilled this year. (The book, a generalized guide to growing flowers, has sold 44,000 copies.) But the magazine work also provided her with an excuse to call up veteran growers and ask them about her own business, which was struggling. One of those calls — to an Idaho grower named MaryJane Butters — would not only change her life but also, because of how she applied the advice, have a ripple effect across the cut-flower world. Benzakein says Butters told her: Be the face of Floret Flowers. Nobody cares about your brand or logo — they want to know about you, so make your picture the homepage of your website. Benzakein, who is naturally introverted, was distressed by everything she heard. “It was exactly the opposite of what I wanted to do,” she says. “I wanted to hide.” But Benzakein says Butters’s other advice was to replace the Floret logo at the bottom of her emails with a picture of herself and “tell me what happens.”

What happened was that Benzakein emailed the regional floral buyer at Whole Foods in Seattle and got an immediate reply. The next day, she brought a bouquet to the buyer, who said, “Can I have 500 of these in time for Mother’s Day?”

“I thought, Oh my friggin’ God,” she remembers. “That was a huge turning point.” By 2008, Benzakein was selling to the store on a weekly basis — her picture, the same one from her homepage, displayed above the floral department — and to meet demand, she leased additional land from a neighbor. She now had two acres.

Then, in August 2013, she met Amy Merrick, an influential Brooklyn florist and blogger, whom Benzakein had come to know through emails. Over the past decade, there’s been a revival in natural floral design — urns teeming with blooms and vines that nod to a pastoral lifestyle — as an alternative to corporate bouquets made with imported flowers pumped with chemicals. Like any trend fueled by Instagram, it has produced stars, among them Chezar in New York, Sarah Ryhanen of Saipua in Brooklyn, and Max Gill in Berkeley. The new floral artisans provide a constant stream of inspiration on their social-media feeds as well as in their workshops.

So although Benzakein suggested it, she still found herself unnerved when Merrick agreed to come out to Washington and lead a weekend workshop with her, for which guests would pay $1,650, accommodations not included. Until then, Benzakein, who is tall and boyishly lean — a ballet dancer in muck boots — had kept Floret off limits to visitors. She felt her house was too close to the greenhouse she and Chris had built and the garage where she taped up photos of Chezar’s arrangements so she could master those sweeping shapes. Despite her fears, the visit proved a success as well as a revelation: “Amy was just gushing about what she saw.” On the last evening, in a friend’s restored barn, the two staged a flower-strewn dinner. “It was the first time,” says Benzakein, “that I saw all of our hard work, but it was now elevated — it wasn’t a grocery-store bouquet.” The event was a watershed in another way: Benzakein began holding “intensive” introductory farming and floral workshops — five the next year, then six. In 2016, she held seven workshops, for which the median price per slot was $2,500 (prices varied depending on workshop type). There were 175 slots in all. From a small-farm perspective, the economics were staggering. The Benzakeins’ two-acre operation brought in more than $400,000 from workshops in one year. They sold out in minutes. In October 2015, when registration opened for the coming year, traffic crashed the Floret site.

So on October 17, 2016, when registration opened for some 100 slots, people around the world positioned themselves at computers shortly before 10 a.m. PST. In the middle of the night in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia, a florist named Lyndal Gubbels waited. In San Francisco, Chelsea Jurado, a bubbly young woman who runs a floral company with a friend, went “back and forth” in her mind until 9:59, “as the price tag was more than I could justify indulging in myself.” At ten, she clicked buy. And in New Jersey, Amy Gallo Gofton, the vice-president of design at Kate Spade, had asked her husband to sign up for her, since he works at home. He went on the site at ten, then the phone rang. “When he went back to the computer, there was literally one slot left,” Gofton told me later. “I didn’t know I was signing up for the hottest thing in the industry.” In all, there were some 3,000 buy attempts on the Floret site.

I first became aware of Erin Benzakein’s appeal last summer, when I followed her on Instagram (she now has more than 438,000 followers). I was not the only person struck by her radical openness and her willingness to share her family life, as well as everything she knew about farming, almost to a fault. Her business was blooming at the exact moment the ethic of organic, local farming was making its way to the flower world. She also produced fantastically lush, long-stemmed blooms — the kind of flower that made it clear she was a good grower as well as a good marketer.

At the time, I was working on a flower farm in the Hudson Valley. The farmer, Angela DeFelice, was teaching me to farm. There is none better. But one day a young florist breezed into the barn to pick up wedding flowers, and we got to talking about the workshops. She told me that, for a designer, having your name linked to Floret can be really helpful. It was an enjoyable, knowing conversation, like one you might have at a New York party — about a new chef or Miuccia’s strategy at Prada — but for that reason it also made me squeamish. Not many beginning farmers could afford the workshops. On the other hand, Benzakein was obviously a woman of guts and intelligence who, at 37, had mastered everything she’d set out to achieve — a farm, a brand, a book, lately a seed business — on two acres of land. In early June, I flew out to Seattle.

Although it’s tempting to see parallels between Benzakein and Martha Stewart — both have great taste, both are attractive, both are businesswomen above all else — Floret reflects ideas that have emerged since Stewart first bread-crumbed her methods for others to follow. Ideas like directness, efficiency, community. For instance, to make it easier and cheaper for brides to order flowers, Floret came up with an “à la carte” menu that allows them to order bouquets and centerpieces as needed and not have to meet the $3,000 full-service minimum. It’s highly profitable for Floret, says Benzakein, and it’s realistic.

Efficiency, of course, reigns in the land of beets and ranunculuses. Indeed, knowing that you can grow very profitably on an acre or two — by using intensive planting techniques and focusing on premium crops — makes small-scale farming attractive, according to Jean-Martin Fortier, a Quebecois farmer-author. Fortier surprised skeptics several years ago when he revealed that his one-and-a-half-acre garden brought in more than $100,000 annually. Floret has taken the same “intensive” approach, with similar results, though not without soul-searching. At one point, the Benzakeins came very close to buying a much larger farm, 80 to 100 acres. Benzakein had found there was enormous interest among out-of-state florists in having Floret’s flowers air-shipped to them.

“But as we sat on it longer, we thought, Why not teach people in all these local communities to grow flowers?” she said. “Connect farmers and florists together and take out the middleman. Why not just work together?” We were sitting in the dining room of a friend’s farmhouse, loaned for the workshops because the property has a large barn — the same one where Benzakein and Merrick held the first workshop. Out the windows, in the distance, were the North Cascades. I had arrived the day before. A group of helpers, most of them florists from around the country who assist during the workshops, were going in and out of the barn, where a corner was massed with buckets of cut roses, peonies, poppies, irises, anemones, calendula, spirea, delphiniums, mint, and honeysuckles, all waiting for the guests to arrive and dip their hands in. “I’m not interested in taking it all or dominating,” Benzakein told me. “Really, I want it to be a win-win for everyone, so that’s why we went deep into education.”

She would be the first to say that, in the beginning, she wasn’t thinking of community power or taking out the middleman or any of the qualities that have inspired so many to become farmer-florists. (The Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers says its membership has doubled in the past five years.) But by sharing what she knows, she has influenced other farmer-florists to do likewise. Floret’s workshop manuals contain an impressive amount of information, like per-acre earnings.

After my initial skepticism about spending a weekend with 25 women arranging flowers, I softened quickly. First, most of them were really good at it. Working alongside them makes you get better, and you gain respect for people craving more fulfillment than their careers provide. (The number of “dreamers” — that is, non-farmers and non-florists — attending the workshops has increased markedly in the past two years.) “It’s like a drug,” a corporate executive said as a bunch of us met for dinner at a local bar. “I can create something and feel good about it. It’s not against sales and numbers, and you’re not going to be benchmarked on it next year.”